The Race for the Next Global Economy: Where is Africa's place?

McKinsey recently published a report which predicts the next arenas of global economic competition. The report identifies a set of industries expected to drive a significant share of future growth. In this article, I examine why meaningful participation in these arenas is likely to remain limited for many African economies, and how current patterns of engagement reinforce a spectator role, as well as what strategic choices would be required to move beyond adoption toward deeper capability and value creation.

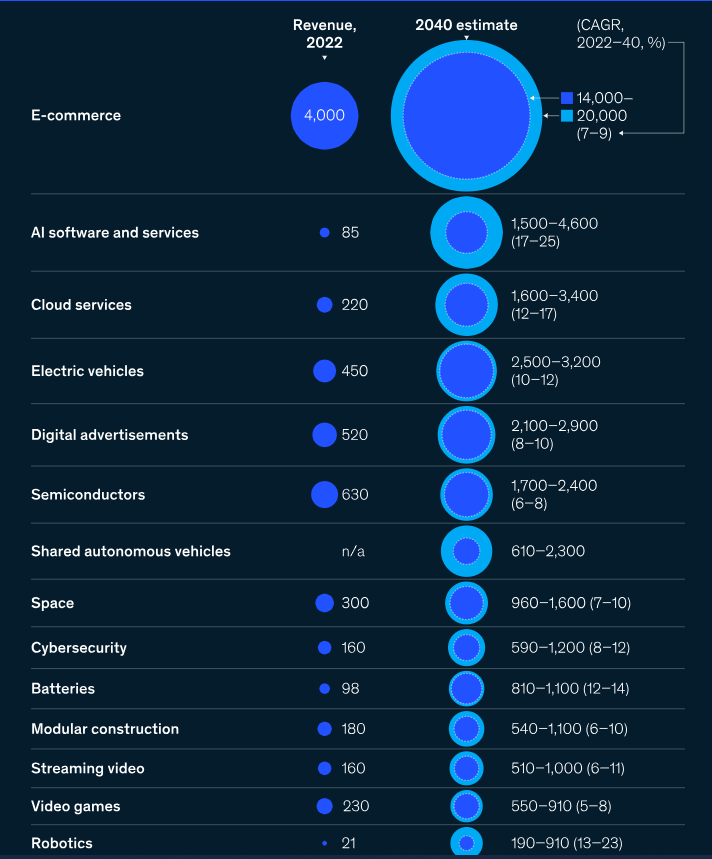

The global management consulting powerhouse’s recent mapping of the next arenas of global competition is quite astounding for both its scale and its analytical confidence. McKinsey’s analysis predicts that by 2040 a relatively small group of fast-growing sectors could account for close to one third of global GDP growth.

Some of the key sectors cited in the report include artificial intelligence software, cloud services, semiconductors, electric vehicles, cybersecurity, robotics, space technologies, and biotechnology. This pattern suggest that economic power in the coming decades will likely be concentrated within a limited set of technologically intensive industries. What remains less explicit, however, is the question of who is positioned to participate meaningfully in this concentration of growth. Let's unpack it together.

Who is positioned to compete within them, and who will remain on the sidelines?

For most African economies, the uncomfortable answer is that participation in these arenas remains limited. Growth projections alone do not translate into opportunity. These arenas demand deep technological capabilities, large pools of capital, dense innovation ecosystems, and institutional capacity that takes decades to build. Without these foundations, engagement tends to occur downstream, through consumption, implementation, or data extraction, rather than through ownership, design, and value capture.

The first angle worth examining is the structure of capability requirements. Many of the highlighted arenas rely on advanced software engineering, high-performance computing, semiconductor design, systems integration, and complex regulatory coordination. These capabilities are cumulative. They depend on strong universities, research infrastructure, industrial linkages, and long-term investment in skills. In contexts where education systems are under strain and research funding is volatile, firms face a steep climb to enter these spaces meaningfully.

McKinsey estimates that as much as 34% of global GDP growth will come from a handful of future arenas, but without deliberate capability building, Africa’s role in that growth will largely be to consume it, not shape it.

A second angle concerns capital intensity and investment dynamics. Several arenas are shaped by escalating investment races. Cloud infrastructure, chip fabrication, electric vehicle manufacturing, and space technologies demand upfront investments measured in billions. Returns emerge over long horizons and depend on scale. African financial systems, which are often risk-averse and liquidity-constrained, struggle to support this kind of sustained capital mobilisation. The result is participation through foreign subsidiaries, licensing arrangements, or procurement contracts rather than domestic industrial growth.

A third angle relates to value chains and control points. Even where African firms and governments adopt frontier technologies, ownership of core platforms, standards, and intellectual property tends to sit elsewhere. Digital advertising, e-commerce, and AI services illustrate this pattern clearly. Local markets generate data, revenue, and users, while strategic control remains concentrated in a handful of global firms. This shapes who captures value and who sets the rules of the game.

Finally, there is a policy dimension that deserves more attention. Much of Africa’s digital and innovation policy focuses on adoption, diffusion, and entrepreneurship at the margin. These are important goals, yet they rarely engage with the harder task of building production capability in high-stakes arenas. Without deliberate choices about which arenas to enter, at what level, and with which institutional support, countries risk spreading limited resources thinly while remaining structurally dependent.

The McKinsey framework is useful precisely because it forces a reckoning with scale and direction. The next arenas of competition are taking shape rapidly. For African economies, the strategic challenge lies in moving beyond passive participation and asking a sharper question. Which parts of these arenas can be shaped locally, under what conditions, and with what long-term commitment to capability building? Growth will happen regardless. Whether it reshapes domestic economies or simply passes through them remains an open choice. Read the full report here.

3 comments have been added to this post

Leave a Comment

Subscribe To My Weekly Newsletter.

Stay updated on the latest insights in innovation, data science, and digital transformation. Subscribe to receive valuable content, industry trends, and actionable strategies delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe